Lumbar Laminectomy

Lumbar laminectomy is a surgical procedure to relieve discomfort, cramps, pain, tingling and numbness in the buttocks or legs caused by pressure on the spinal cord, the cauda equina or spinal nerve roots.

The aim of surgery is to remove the pressure by opening the spinal canal and widening it from the back. The surgeon removes bone and other tissue pressing on the affected nerves, providing more space for the nerves and reducing any irritation and inflammation.

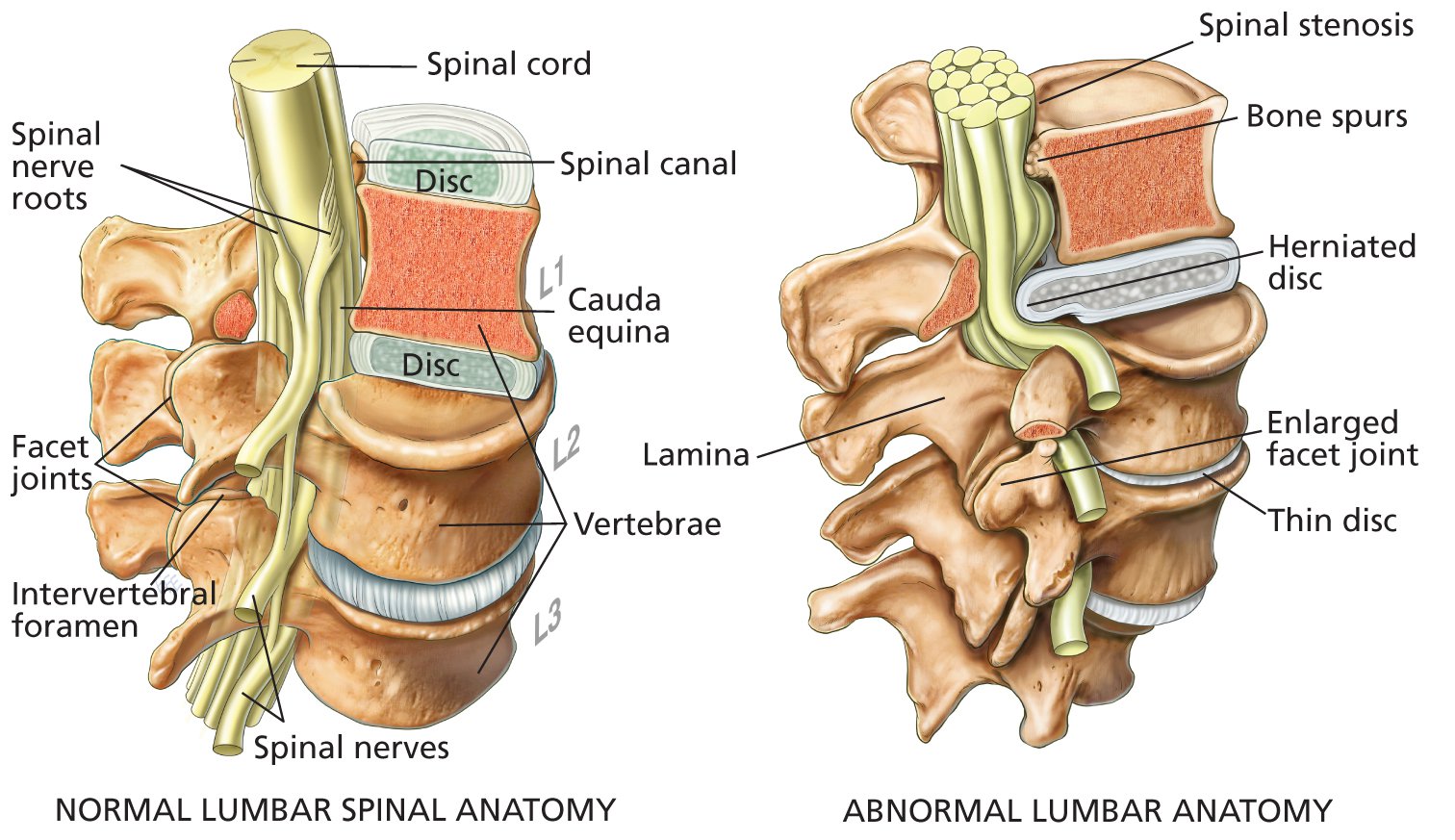

Laminectomies are typically performed to treat lumbar spinal stenosis. This is a narrowing of the spinal canal that contains the spinal cord and the spinal nerves that arise from the spinal cord, as shown in the illustration (above). At the lumbar level of L1, the spinal cord becomes a nerve bundle called the cauda equina.

Spinal stenosis occurs mainly in older patients due to age-related:

- osteoarthritis of the spine and degenerative changes in the facet joints of the lumbar vertebrae; facet joints link vertebrae together, giving the spine flexibility, stability and strength, but are susceptible to arthritis, just like other joints in the body

- enlargement of the facet joints of the vertebra

- thickening of facet-joint tissue due to chronic inflammation

- formation of bone spurs (osteophytes) on a vertebra caused by friction between ageing, inefficient facet joints

- thickening, hardening and calcification of ligaments of the spine

- thinning of intervertebral discs, which leads to less space between vertebrae, resulting in smaller intervertebral foramen for spinal nerves to pass through; if a foramen becomes too small, its spinal nerve will be compressed or “pinched”

- herniated or bulging discs

- slippage of one vertebra over another (spondylolisthesis). It occurs usually due to age-related degeneration but sometimes is seen after trauma to the lumbar spine. Spondylolisthesis most commonly occurs between the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae (L4-L5 level) and the fifth lumbar and first sacral vertebrae (L5-S1 level).

All of the above conditions slowly cause decreases in the space around the spinal nerves, increasing the risk of compression.

Other conditions that can lead to spinal stenosis include:

- rheumatoid arthritis of the spine

- a spinal tumour

- Paget’s disease, which causes weak and deformed bones

- acute trauma

- congenital spinal stenosis (existing from birth); symptoms can develop easily in these patients, even when age-related changes or physical stresses are fairly minor

- scoliosis (curvature of the spine)

- achondroplasia (a hereditary condition of abnormal bone growth).

The most common symptom is “neurogenic claudication”. This is a painful cramping discomfort and/or weakness which can be in both or one calf, thigh, and buttock. It is usually provoked by walking or prolonged standing, and is relieved by rest and/or a change of position (usually flexion at the waist).

If a lumbar spinal nerve is compressed, the most common symptoms are:

- sciatica – a syndrome of pain in the lower back and hip, radiating down the buttocks to the back of the thigh and into the leg; most cases of spinal stenosis that cause significant symptoms affect the sciatic nerve, a large nerve that originates at L4, L5 and the sacrum

- persistent discomfort or pain in one or both legs

- dull to severe aching pain in the lower back or buttocks

- numbness and tingling in one or both legs; occasionally the patient may have muscle weakness.

Symptoms can range from mild and intermittent to severe and debilitating. Uncommonly, a few patients have problems with urinary or bowel continence and function. In the most serious cases of pressure on the cauda equina, bladder and bowel control may be severely impaired or lost. Such cases are rare.

Talk to your surgeon

This guide is intended to provide you with general information. It is not a substitute for advice from your surgeon and does not contain all the known facts about lumbar laminectomy. This information will change with time due to clinical research and new therapies.

If you are not sure about the benefits, risks and limitations of lumbar laminectomy, or terms used in this guide or related matters, ask your surgeon. Read this information carefully. Technical terms are used that may require further explanation by your surgeon.

Write down questions you want to ask. Your surgeon will be pleased to answer them. Seek the opinion of another surgeon if you are uncertain about advice that you are given. Use this guide only in consultation with your surgeon.

Consent form: If you have surgery, your surgeon will ask you to sign a consent form. Before signing, read it carefully. If you have any questions, ask your surgeon.

Costs of treatment

Your surgeon can advise you about coverage by public health insurance, private health insurance and out-of-pocket costs. Ask for an estimate that lists the likely costs. As the cost of actual treatment may differ from the proposed treatment, the final account may vary from the estimate. It is best to discuss costs with your surgeon before treatment rather than afterwards.

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnostic imaging can provide your surgeon with important information about vertebrae, other spinal structures and abnormalities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computer tomography (CT), X-ray examination and a spinal myelogram can often reveal the anatomy of the vertebrae and the precise location of abnormalities. One or more of these tests may be necessary for accurate diagnosis.

Your surgeon will examine you to determine your strength, reflexes, ability to feel pain, and ability to move. You will be asked about pain, numbness, weakness, previous similar symptoms, and any bowel or urinary problems.

TREATMENT OPTIONS

- “Wait and see” – Damaged or inflamed tissue may heal with time. Over several weeks or months, or sometimes longer, symptoms can subside. Patients with mild symptoms often do well without surgery. Most patients with back pain do not require surgery.

- Medications – oral medications such as various analgesics (paracetamol, codeine, Digesic, Tramadol, Endone) can provide short-term pain relief. Non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and corticosteroids can reduce inflammation and provide pain relief. Anticonvulsant medication (Tegretol, Epilim, Neurontin, Lyrica) and some antidepressive medication can also be used to treat nerve pain.

- A nerve sheath injection (foraminal block) – This is the use of local anaesthetic with cortisone injected in the area of the compressed spinal nerve. This can provide significant medium-term, temporary relief. While relief typically lasts for days or weeks, this can be long enough for symptoms to subside and for surgery to be delayed or avoided.

- Epidural steroid injection (ESI) – This delivers pain-relieving anti-inflammatory medication close to the source of pain. ESIs can be very effective, but relief tends to be temporary, ranging from one week to one year. If symptoms are relieved by an ESI, then the patient is likely to have a good outcome from a laminectomy, if surgery becomes necessary.

- Physical therapy and specific exercises can be helpful if symptoms are not severe. Mild exercise can assist muscle tone, core strength, fitness, posture and flexibility of the spine. While often helpful, spinal-stenosis exercises are not curative.

- Other conservative treatments can include activity modification, bed rest, back bracing, weight loss and lifestyle changes.

- For patients whose symptoms persist despite medical and conservative treatments, a laminectomy may be needed. Surgery can often be an appropriate first option in patients with severe or worsening symptoms. Outcomes from surgery are usually better when the patient has early diagnosis and the surgery is undertaken before symptoms worsen.

Your medical history

Your surgeon needs to know your medical history to plan the best treatment for you. Tell your surgeon about any health problems you have. Some may interfere with treatment, surgery, anaesthesia or recovery.

Before surgery, tell your surgeon if you have had:

- an allergy or bad reaction to antibiotics, anaesthetic drugs or any other medicines, surgical tapes or dressings

- prolonged bleeding or excessive bruising when injured, or a family history of excessive bleeding

- recent or long-term illness, and any previous surgery.

Give your surgeon a list of ALL medicines you are taking and have recently taken. Include medicines prescribed by your family doctor, other doctors and those bought without prescription. If you need surgery, your surgeon may ask you to stop taking some medicines for a week or more before surgery, or you may be given an alternative dose. Discuss this carefully with your surgeon.

Smoking

Patients who smoke must stop for at least three weeks before surgery and three weeks after surgery. It is best to quit because smoking interferes with healing and recovery. After surgery, smokers have increased risks of infections, heart and lung complications, and deep venous thrombosis (DVT).

Candidates for lumbar laminectomy

When deciding if surgery is an appropriate option for you, your general health and the severity of symptoms are the most important factors to consider.

For most patients, surgery is an option if they have spinal stenosis or a condition related to spinal stenosis, and have:

- severe and persistent leg pain that is disabling or significantly limits normal daily activities

- weakness or numbness of the legs or feet

- difficulty walking or standing, or

- bowel or bladder control problems.

Surgery is typically not an option when:

- symptoms are improving

- pain is not severe

- leg and lower-back symptoms are not due to spinal stenosis or a related condition

- doses of pain killers are reasonable

- physical therapy or exercise reduces pain and discomfort

- another medical condition is likely to complicate surgery.

The decision to have lumbar laminectomy

As you make the decision whether or not to have surgery, make sure that you understand the risks, benefits and limitations of lumbar laminectomy.

There can be risks if you do not have surgery to relieve compression of a lumbar spinal nerve because further damage to it may occur. In some patients, the most serious complications can include further pain, numbness, paralysis or loss of bladder or bowel control.

Your surgeon cannot guarantee that treatment will meet all your expectations and that it has no risks. Only you can decide if surgery is right for you. If you have any questions, ask your surgeon.

LUMBAR LAMINECTOMY SURGERY

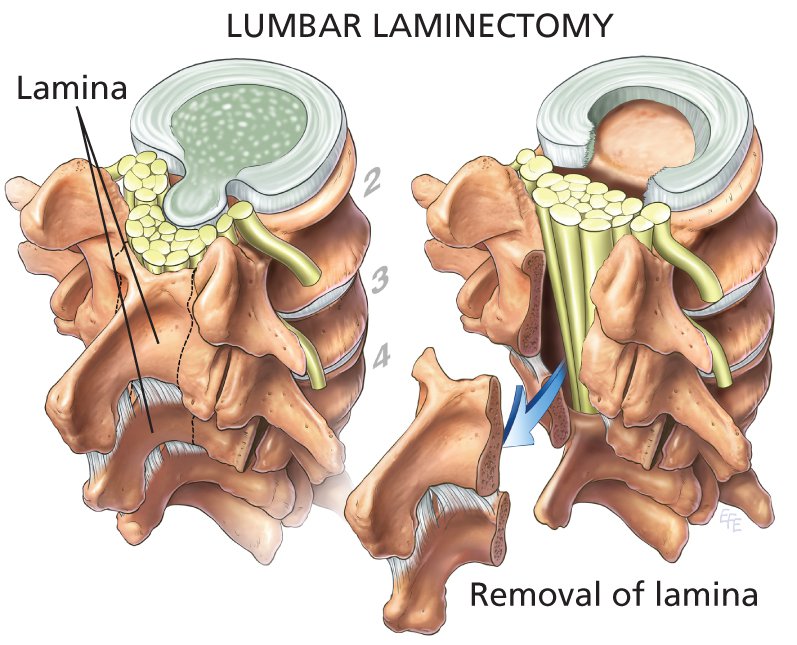

The aim of laminectomy is to remove enough of the bony lamina so that the spinal cord or the cauda equina and spinal nerves are decompressed and symptoms are relieved.

A skin incision is made over the spine, directly opposite the vertebrae related to the symptoms. Muscles and fat tissue on the left and right are pushed aside from the lamina so the surgeon can see and access the vertebra. An X-ray film may be taken to make sure that the correct vertebrae have been selected.

The surgeon may remove the bony spinous process using special instruments. Sections of lamina are removed using a surgical drill. In most cases, removal of lamina does not affect the stability or mobility of the spine.

A large ligament called the ligamentum flavum is removed to reach the spinal canal. At this point, the surgeon can see the spinal canal and the spinal nerve roots, and the cause of compression can be identified.

Pressure on spinal nerves and the spinal cord (or cauda equina) is relieved by:

- enlargement of the spinal canal

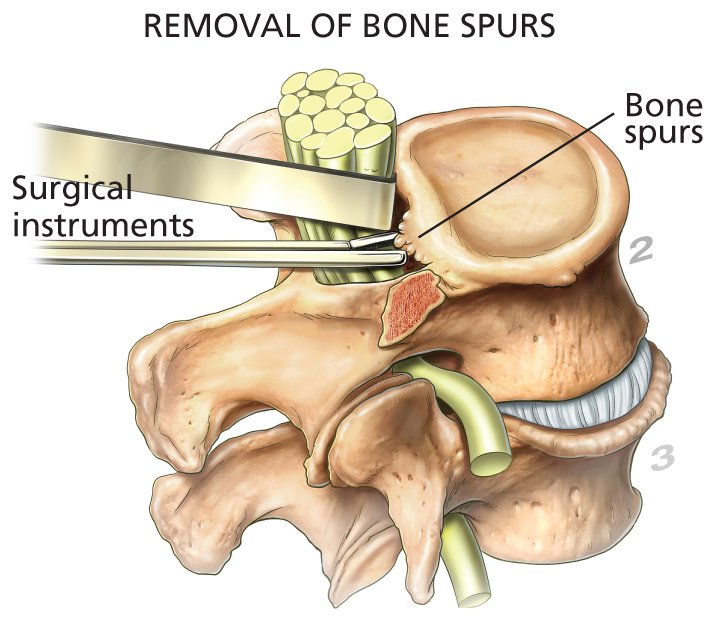

- removal of any bone spurs

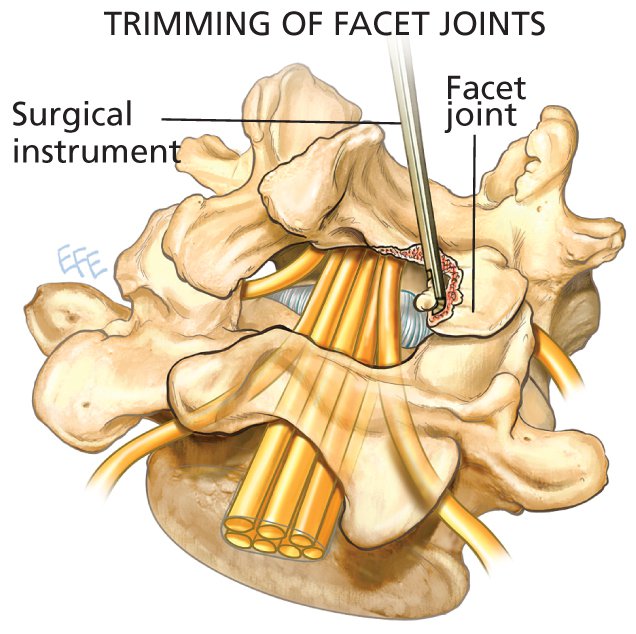

- trimming the facet joints (bone that lies directly over spinal nerves) so that the intervertebral foramen are widened, creating more space for an affected spinal nerve

- removal of any tumour or cyst

- removal of any disc tissue that may be impinging on a spinal nerve, the spinal cord or the cauda equina.

Spinal fusion

Laminectomy can be done with or without fusion and with or without surgical removal of a portion of an intervertebral disc (discectomy). Your surgeon can explain whether fusion or discectomy is likely.

If your surgeon has to remove a lot of the facet joints and lamina, or needs to correct or prevent spondylolisthesis (the slippage of one vertebra over another), a “spinal fusion” may be needed to support the vertebrae. The objective is to keep the spine stable and strong.

Fusion is performed by placing bone grafts between vertebrae to create a solid section. Metal implants consisting of small plates and screws are usually needed for vertebral strength while the bone grafts heal, grow and become strong. These implants are usually left in place.

After the spinal surgery is completed, the surgeon closes the incision with metal staples or sutures. In some cases, a drain may be placed in the operated area to drain excess fluids. It is usually removed in one or two days.

Lumbar laminectomy typically takes about one to two hours to complete. If fusion is also required, the total procedure will be longer.

Laminotomy

In some cases, only a very small portion of the lamina has to be removed in order to provide relief for a spinal nerve. This is called a laminotomy.

Prognosis

Some patients may experience immediate pain relief, while in others resolution of pain may occur slowly over several weeks or months. Muscle strength may improve over a few months but may not be completely restored. Numbness often takes many months to improve. The ability to undertake physical activities is usually improved.

The degrees of improvement of discomfort, pain, numbness, weakness and related symptoms are usually related to how long the patient had symptoms prior to surgery, and whether or not one or more spinal nerves were damaged.

The likelihood of benefits from the surgery depends on many factors. Your neurosurgeon can provide an assessment of the chances of success in your case.

If symptoms were due to ageing, they may recur several years after surgery because the degenerative processes of spinal stenosis continue. The patient may need to have surgery again.

AFTER SURGERY

As you awaken in the recovery area, nursing staff will check your blood pressure, pulse, leg strength and general well-being. You may have a urinary catheter to help empty your bladder.

Expect to have some pain at first. People have different levels of pain perception and tolerance. You will be given medication to relieve pain and discomfort.

With assistance, walk as soon and as often as possible. Many patients find that they can walk a little on the day of surgery. Walking helps to improve recovery and reduce the risk of blood clots in the deep veins of the legs (deep venous thrombosis, DVT). Most patients are discharged one to three days after surgery.

You are discharged when you:

- have stable vital signs

- can walk on your own

- can eat and drink without nausea

- have normal control over your bladder

- have recovered normally from the anaesthetic, and the operated area is healing well.

Some discomfort in one or both legs may remain for a couple of days after surgery. This is due to swelling of the operated site. As aspirin and anti-inflammatory pain relievers may increase the risk of bleeding in the operated site during healing, take these only on the advice of your surgeon. Recovery in patients who have had a spinal fusion may be a little slower.

Recovery at home

- Bending and twisting should be gentle and as little as possible.

- Do not carry anything heavy.

- Before you lift and carry anything heavy, discuss with your surgeon the best ways to lift and carry.

- Dressing is easier with slip-on shoes.

- Daily light exercise and walks help to reduce pain and hasten recovery. Increase slightly the distance walked daily. Have reasonable goals. Don’t do too much.

- For at least one or two weeks after surgery, get assistance at home.

- To relieve pressure on the operated site, do not sit or stand in one position for long periods.

- Do not sleep too much, but get adequate rest. You may find that you wake-up having a sore back. A warm shower or brief walk may help to relieve it.

- Your surgeon can advise you about your return to work. It depends on how quickly your back and leg symptoms are resolving, your general recovery from surgery, and your occupation.

- A specific rehabilitation program may be recommended.

POSSIBLE COMPLICATIONS OF LUMBAR LAMINECTOMY

All surgical procedures are associated with some risk. Despite the highest standards of surgical practice and care, complications are possible.

It is not usual for a surgeon to dwell at length on every possible side effect or rare, but serious, complications of any surgical procedure. However, it is important that you have enough information to weigh up the benefits, risks and limitations of spinal surgery. Most patients will not have complications, but if you have concerns about possible side effects, discuss them with your surgeon.

Any discussion of frequency of risks or benefits (for example, one patient in 100, or “rare” and so on) can only be estimates as the outcomes of clinical research can vary widely. Such outcomes can depend on many factors, such as the surgical methods, equipment, surgeons’ experience and data collection, among others.

The following list of possible complications is intended to inform you, not to alarm you. There may be others that are not listed.

General risks of surgery

- About one patient in 100 develops an infection of the operated site that requires treatment with antibiotics. A deep infection may require a return to theatre to treat and drain the infection.

- Excessive bleeding; rarely, a blood transfusion may be needed.

- A blood clot that develops in a deep vein in a leg (deep venous thrombosis, DVT) may travel to the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism. This complication is not common but can be life threatening.

- Complications due to the anaesthetic.

- Unforeseen complications, such as pneumonia, stroke or heart attack, may or may not be directly related to the surgery or anaesthesia but could result in death, although this is rare.

Specific risks of laminectomy

- A small tear in the thick tissue (dura) covering the spinal nerve roots is a common risk. A tear allows cerebrospinal fluid to leak out. It may occur in about one of every 20 patients. While a leak usually heals quickly after surgical repair done at the time of the original operation, further surgery may be needed.

- Instability of the spine may require further surgery to fuse the affected vertebrae.

- You may not get the degree of relief you expect. Although the laminectomy may be a surgical success, your surgeon cannot predict with certainty how the spinal nerves will heal after surgery. Pain, numbness, tingling and muscle weakness may not improve with surgery or may improve only slightly.

- Despite the surgeon’s expertise, further damage to a spinal nerve may be caused by surgery in a few cases. If the nerve is already damaged, surgery could worsen the injury to it, causing increased pain, numbness and weakness in the legs, loss of bladder and bowel function (incontinence), and impotence in males.

- Scar tissue can form near a spinal nerve during healing. It can restrict the free movement of the nerve and can press on it, causing pain or discomfort.

- A blood clot in the spinal canal may require drainage and more surgery.

- Temporary or permanent paralysis of the legs (paraplegia) occurs very rarely. The most likely cause is probably due to formation of a haematoma (large blood clot) in the spinal canal that compresses the cauda equina, damaging it. Sometimes the cause is not known. If the legs suddenly become weak and numb and urine cannot be passed, urgent surgery may be needed to remove the clot.

- Raised, itchy and reddened scars from the skin incision (keloid or hypertrophic scars). These can be annoying but are not a threat to health.

- People who have had previous spinal surgery in the same area (revision surgery) have greater risks of complications, primarily due to the formation of scar tissue around the nerve roots.

- Other complications may be caused by a spinal fusion or discectomy undertaken during the laminectomy.

Report to your surgeon

When you are recovering from the surgery, contact your surgeon at once if you have any of these signs or symptoms:

- fever greater than 38°C or chills

- redness or increasing pain at the incision

- persistent drainage or ooze from the incision

- stitches or staples come out

- pain, swelling or redness in one of your legs

- increasing pain or numbness in your legs, buttocks or back

- the bandage becomes soaked with blood

- a severe headache, or

- if you have any questions or concerns.

Go immediately to the nearest hospital emergency department if you:

- have sudden shortness of breath, which may or may not be accompanied by chest pain (this could be a sign of a blood clot in the lungs, pneumonia or other heart and lung problems)

- lose control of your bowel or bladder, or if you are unable to urinate

- are unable to move your legs (this is a serious sign of nerve compression or cauda equina syndrome).

Edition number: 2, 01 December 2015

This Guide, or portions of it, should not be reproduced in any electronic, online or hard-copy format.

Mi-tec Online©